|

| photo Beyond my Ken |

The passing of the Federal Reserve Act in 1913 resulted in

the establishment New York City's Federal Reserve Bank within a year. Starting out in leased space at No. 62 Cedar

Street, the bank’s responsibilities and roles rapidly multiplied. When the United States was pulled into the

First World War, the Federal Reserve Bank became the government’s fiscal agent

and oversaw the sale and distribution of war bonds.

As the bank grew, additional offices were leased until in

1918 it was spread throughout lower Manhattan in six locations. That year, in May, the Federal Reserve Bank

purchased the first property in what would be the site of a monumental banking

structure. The aggressive buying

continued until, on January 11, 1918, the Real Estate Record & Builders' Guide reported on the purchase of the

Fahys Building, at Nos. 29-31 Liberty Street.

The paper called it “Substantial enlargement of the site acquired last

May.” The Federal Reserve Bank now

controlled “twenty buildings of various heights, but principally obsolete

structures, aside from the one just purchased and the former home of the

Lawyers’ Title & Trust Company, an eleven-story structure of modern

construction.” Some of the Federal

Reserve Bank’s offices were already located in the Lawyer’s Title

building. The Bank had spent nearly $5 million in accumulating the real estate.

Within the week the Bank was ready for Phase 2. On January 18 The Real Estate Record &

Buiders' Guide said “Plans for this structure have not been definitely decided upon, but

it has been state that the designers will be selected through a paid competition

that will include the best architectural talent of the country.” The periodical felt it was "doubtful” that the

construction could cost less than $10 million.

The New-York Tribune hinted at the guidelines given to

hopeful architects. The Trustees “also

explained that the structure would have to be dignified, as no sensational type

of building would be entertained by the bank.”

Consideration of the many architectural submissions took

nearly a year; but on November 7, 1919 the New-York Tribune reported on the

decision. And in doing so the newspaper

announced its surprise at the 14-story design.

“It has been the general impression that it would be not more than four

stories. Apparently the architects who

were asked to submit plans for the bank building were not limited as to height.”

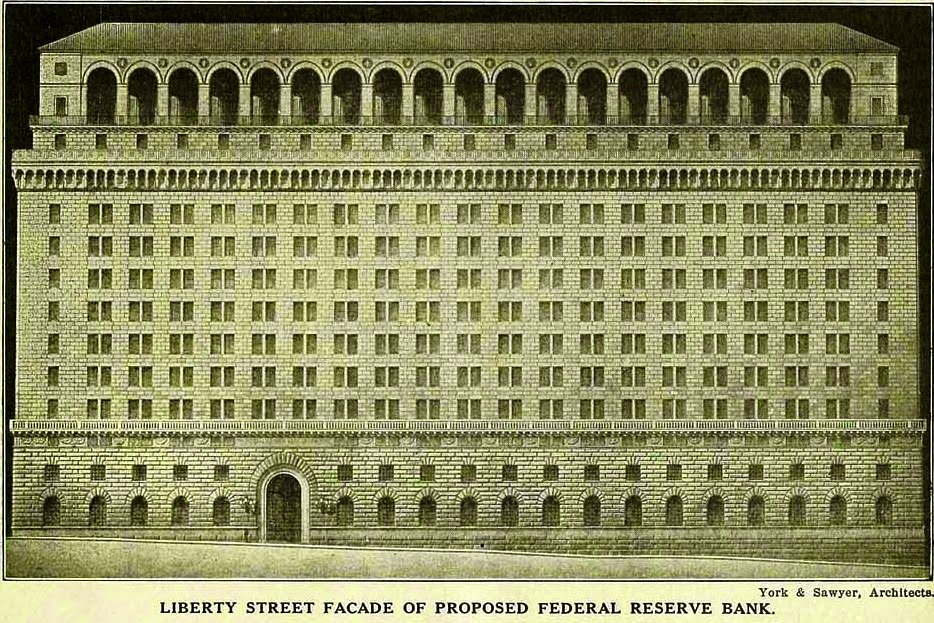

On December 13, 1919 a sketch from the winning firm, York

& Sawyer, was made public. The

architects worked with an irregular plot, bounded by Nassau Street, William

Street, Maiden Lane an Liberty Street, that sat on a steep incline.

Their design, according to The Guide, was “a modified Florentine

style of architecture, adapted to American ideas and the peculiarities of the

downtown business district." In fact,

Sawyer & York recalled the imposing banking houses of Florence in an effort

to impart stability and safety. The

architects borrowed heavily from the Palazzo Strozzi.

On November 16 the New-York Tribune said “The designs

submitted by York & Sawyer were accepted as providing the kind of

serviceable, dignified loft building which the directors wanted, and now the

builders are awaiting the word to rip and tear away the old landmarks which

have encumbered the block for years and years.”

The planned structure would be the largest banking building

in the world. The Guide now revised its

construction estimate—saying it might cost as much as $15 million. The Federal Reserve Bank worked with the City

to address the narrow, irregular streets surrounding the site; which would

negatively impact the proposed building.

The New-York Tribune reported “Ten feet are to be added to

the width of Nassau Street at Maiden Lane and eight feet to Liberty Street at

Nassau Street, and the hip in the south side of the building and street line of

Maiden Lane is to be straightened. The

space is to be sliced off the Federal Reserve property that the building may

have a better setting and also to eliminate structural defects that would be if

the present building lines were to be the lines of the new structure.”

The newspaper mentioned the grand two-story lobby to

come. “Toward Nassau Street the lobby,

or corridor, will open out into a general reception room, as it will be at this

end of the floor that the executives of the institution will have their

offices. This reception space will be

thirty-four feet wide and seventy-one feet long and, of course, will reach through

two floors of the building. It will be a

magnificent room.”

Each floor of the 15-story structure encompassed just under 32,000

square feet. Plans called for an immense

conference room, engulfing the entire Nassau Street side of the second

floor. The Bank set space aside for

unexpected amenities for the thousands of employees who would be working in the

building. “Above the twelfth floor are

to be located restaurants, promenades, hospital, gymnasium and other recreation

features.”

Propriety mandated that the dining areas for men and women

were segregated. “There will be three

restaurants, or, rather, dining rooms, one for officers of the bank, one for

the men employees and one for the women folks.

The women’s restaurant will be on the thirteenth floor. It will be large enough to seat 700 diners at

one time.” The women’s dining room faced

the loggia, high above street level, where an outdoor Promenade circled the

entire floor.

The wheels of progress, at least as far as construction of

the Federal Reserve Bank was concerned, ground slowly. On July 17, 1921 the Tribune noted that the

nearly $5 million project of removing the existing structures had gotten

underway. By now the cost of the

building had been set at $12 million.

Three years later, in September 1924, the mammoth banking

palazzo was completed. Philip Sawyer stepped

away from norm in creating a polychrome façade by mixing different colored limestone

and sandstone blocks. These were deeply

grooved, adding dimension to the otherwise flat surface.

Sawyer commissioned Polish-born Samuel Yellin to execute the

ornamental ironwork. The architect was

specific in his desires—insisting on Italian Renaissance decorations

appropriate for the Florentine-style structure.

The Philadelphia firm produced ironwork of exceptional craftsmanship,

the most outstanding being the two immense, ornate branched lanterns flanking the

entrance—exact copies of those mounted on the Palazzo Strozzi.

In 1925 the Maiden Lane Historical Society met with officials

of the bank and with York & Sawyer to compose an inscription for a bronze

tablet to be affixed to the façade. On

March 28 it was unveiled; informing passersby who cared to pause about the

history of the site and the origin of the street names.

The bank runs and lost savings that accompanied

the onset of the Great Depression, prompted some to hoard gold. On October 18, 1931 The New York Times noted “There

is no way of estimating even remotely the amount of currency that has been

hoarded in the United States, but some

calculators have placed it between $800,000,000 and $1,000,000,000. It was a problem that the government and the

Federal Serve Bank would soon address.

But in the meantime another problem had been addressed--and

solved--by the reporters of rediscount rates.

On the same page as the article about hoarding, The Times said that

every Thursday afternoon at 3:30 the doors to the executive offices at one end

of the 10th floor of the Federal Reserve Bank Building opened and

the changes in rates were announced.

The problem was that the telephone booths (both of them)

were located at the other end of the hall, several hundred feet away. “In reporting for financial tickers, seconds,

not minutes, count, so that each of the rival organizations posts a man at the

telephones and another at the opposite end of the corridor to receive the

announcement from the spokesman of the Federal Reserve,” explained The Times. “To obviate shouting to their colleagues at

the telephones or engaging in a dead heat down the corridor, the men at the

fountain source of the news have evolved a system of signals which convey the

information quickly and accurately.”

The ingenious system involved hand signals and handkerchiefs. The

men stationed at the telephone booths watched intensely toward the far end of

the hall. If the rate were unchanged, a

handkerchief was waved. If it were

one-half of a percent, a hand was raised.

If the increase amounted to a full percent, both hands were waved. Eugene M. Lokey, the Times writer, joked “If

the day should come when the rate jumps 1-1/2 per cent, the men are to fall to

the floor, and should it be 2 per cent, the plan is to fall kicking

frantically.”

On April 5, 1933 President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed

Executive Order 6102 “forbidding the hoarding of gold coin, gold bullion, and

gold certificates within the continental United States.” Two weeks earlier, realizing that their

hoarding was about to become criminal and subject to prosecution, thousands of

New Yorkers descended on the Federal Reserve Bank.

On March 11 The New York Times reported on the events of the

previous day. “A gold stampede in

reverse, unlike anything within the memory of the downtown financial community,

developed yesterday as repentant hoarders swarmed into the Federal Reserve

Bank.

“Realizing, suddenly, that the hitherto desirable yellow

metal had become ‘hot’—in the underworld sense that its holders are in danger

of punishment—men and women waited in long lines for the privilege of shoving

coin and gold certificates through the tellers’ windows. Extra guards in the corridors shepherded

newcomers into the receiving departments.”

The bank was kept open until 5:00 and $20 million in gold

and certificates was received. That

amount, added to the receipts of previous days, brought the total for the week

to $85 million. It seems that almost everyone in the line had

a good excuse for the gold they had kept in their homes.

“One man who came with a satchel, which a friend helped to

carry, protested that he was not a hoarder, but a patriot, putting gold back

for the good of the country. ‘I am

married,’ he said. ‘I would not want the

shame of hoarding to rest upon my children.’”

Nevertheless, the newspaper noted that it was all a somber

affair. “There was little smiling,

virtually no laughter, and no disorder.”

Two decades after the completion of the Federal Reserve

Bank Building, Sawyer & York were

called back. The bank required a full

five additional floors. With great foresight,

however, the architects had designed the structural plan to support additional

floors if needed. The firm estimated

the cost of the addition to be $750,000—just under $10 million today.

|

| The addition upset the proportions of the structure; but sympathetically melded with the original design. photo by Wurts Brothers, from the collection of the New York Public Libraryy |

The additional floors took out the charming loggia and

promenade; but carried on the general design of the lower bulk of the

building. Even the stonework—truly appreciated

only by workers in high office buildings—continued the multi-colored motif. At one corner a round turret which enclosed a

staircase prompted one passerby to call it “that building with the castle on

top.”

|

| photograph The Market Oracle, March 19, 2011 |

In 1995 the Federal Reserve started a floor-by-floor

modernization initiative. The 15-year

project resulted in renovations that upgraded the infrastructure and technological

functions; while preserving the period details like paneling. Surrounded by glass and steel, York &

Sawyer’s 15thth century banking palazzo captures the fascination of

anyone pausing to take in the “building with the castle on top.”

many thanks to reader Holly Tooker for requesting this post

I love the addition! That curve n the end is so underestimated.

ReplyDeleteSo appropriate for our illegal "Federal Reserve".........an overpowering combination of fortress, prison, and bank vault styled structure. Definitely designed to intimidate.

ReplyDelete***